Electroacoustic Engineer, Brian Johansen, has tested sound in everything from airplanes and cars to refrigerators and satellite launches.

It took over 40 years for someone to come up with a better ear simulator than the 711 coupler originally developed by acoustic engineering pioneers Per Brüel and Gunnar Rasmussen. That someone was Brian Johansen.

Today, he is an Acoustics Engineer at GRAS (Gunnar Rasmussen Acoustic Systems) Sound & Vibration, a sound and acoustics company founded in 1994 by the then-67-year-old Electronics Engineer, Gunnar Rasmussen.

At GRAS, Johansen is involved in developing microphones for measuring sound within industries such as hearing aids, automotive, defense, and aerospace, and for measuring environmental noise.

The ugly speakers had to go

Brian Johansen's love for sound and acoustics started in his childhood, where, as a young music enthusiast, he yearned for a keyboard. He received one as a Christmas gift, and it was then that he realized that, while notes and harmonization did wonders for the mind, the actual sound was equally as important. This became even more evident to him when he played music as a teenager in revues, circuses, and theaters.

"It wasn't just the instruments that had to sound great, it was the ‘richness' of the sound quality that made the total experience," says Brian Johansen.

He labels himself a "nerdy sound engineer" who can get a headache from bad sound. But he has learned that good sound doesn't necessarily go hand in hand with aesthetics.

"My girlfriend fell for me being so nerdy, but unfortunately my speakers had to go, and we settled on a B&O designer compromise," he laughs.

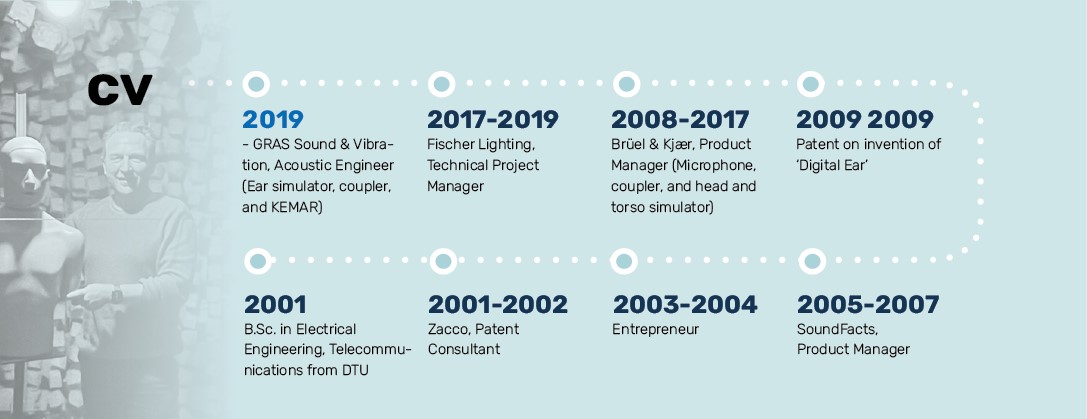

Although his career has taken some twists and turns, sound has always been the common thread, whether as a physics teacher, inventor and patent holder, or tour manager for Danish song stars.

That it was as an engineer that Brian Johansen could turn his passion for sound into a professional career can partly be attributed to the school fatigue he suffered after graduating from high school. Instead of continuing his education, he got an internship at Rhinometric, where they developed products for nasal measurements based on electroacoustics and digital signal processing. Simply put, sound is sent up into the nose, and the reflection can create an internal cross-sectional area, allowing doctors to see why people can't breathe and surgeons to see where to operate.

"It was an alternative to expensive MRI scans. There, I saw that sound could be used for more than 'just' creating moods and that it could be used for practical purposes as well," says Brian Johansen.

One semester at a time

It was also while at Rhinometric that he met an engineer who believed that Brian Johansen should also pursue an engineering career.

"I wasn't particularly keen on studying because high school had been a bit boring, but I decided to give it a shot for one semester at DTU (Technical University of Denmark). And that one semester turned out to be pretty fun, so I took another one, and that was also quite enjoyable," he says.

And so it continued until he held a Bachelor's degree in Telecommunications in his hand.

"I took all the acoustics courses I could get my hands on because that was what interested me."

After a few years "off track" at a patent office where the urge to escape from "suits and ties" steadily grew, Brian Johansen came across a job posting from B&K seeking an employee for an ear simulator in their R&D department. He applied and got the job.

At the time, there was an interest in upgrading the 711 coupler, which had been the standard ear simulator for over 40 years, with new measurements.

"The task was physically impossible because such experiments cannot be conducted on living subjects, as a microphone must be placed where the eardrum is located. Therefore, it had previously only been tested on cadavers," he says.

However, Brian Johansen succeeded in developing a method where, using an oil-based contrast fluid in the ear canal of living subjects, an imprint of an ear canal down to the eardrum could be taken using an MRI scanner. He has since patented the invention, called the "human-like ear simulator."

"It was a completely new method for deriving the geometry of human ear canals. For the first time, there were real imprints from living humans, and we could make measurements that no one had been able to achieve before because it was not technically possible 40 years ago," he explains.

Although it is not the first patent he has received, and his career includes many imprints, the ear simulator project is the one he is most proud of.

"One could not help but look up to Per Brüel (founder of B&K) and Gunnar Rasmussen (former R&D director of B&K and founder of GRAS). They were the big mastodons of their field. To top one of their inventions was quite an accomplishment."